We are showered with gratitude this week as we work to clear debris with the volunteer force mobilized by Habitat for Humanity. We are in Chalmette, Louisiana, part of “Greater New Orleans” swamped by Hurricane Katrina last fall. I’ve been thinking about want and need, about generosity and vulnerability, about our material needs and our more intangible needs. Both offering help and accepting help can be very good and also very hard. We can be benefactors or humble recipients—or sometimes both at once. A fellow volunteer says that she is taking away far more from this experience than she has given. The homeowners we are helping might disagree; our contribution to them is enormous. But their contribution to us, in giving us a place to give and to help and in sharing their hopeful and generous spirit, is also incredibly significant.

Our contribution here may be admirable, but the really courageous people are those we are giving to. Despite surviving an unbelievable regional trauma, they have spirits willing to be helped and willing to give in the midst of receiving. Like Denise, a homeowner who worked alongside us for two days as we gutted her home and tossed her life’s belongings into a fifteen-foot-high debris pile.

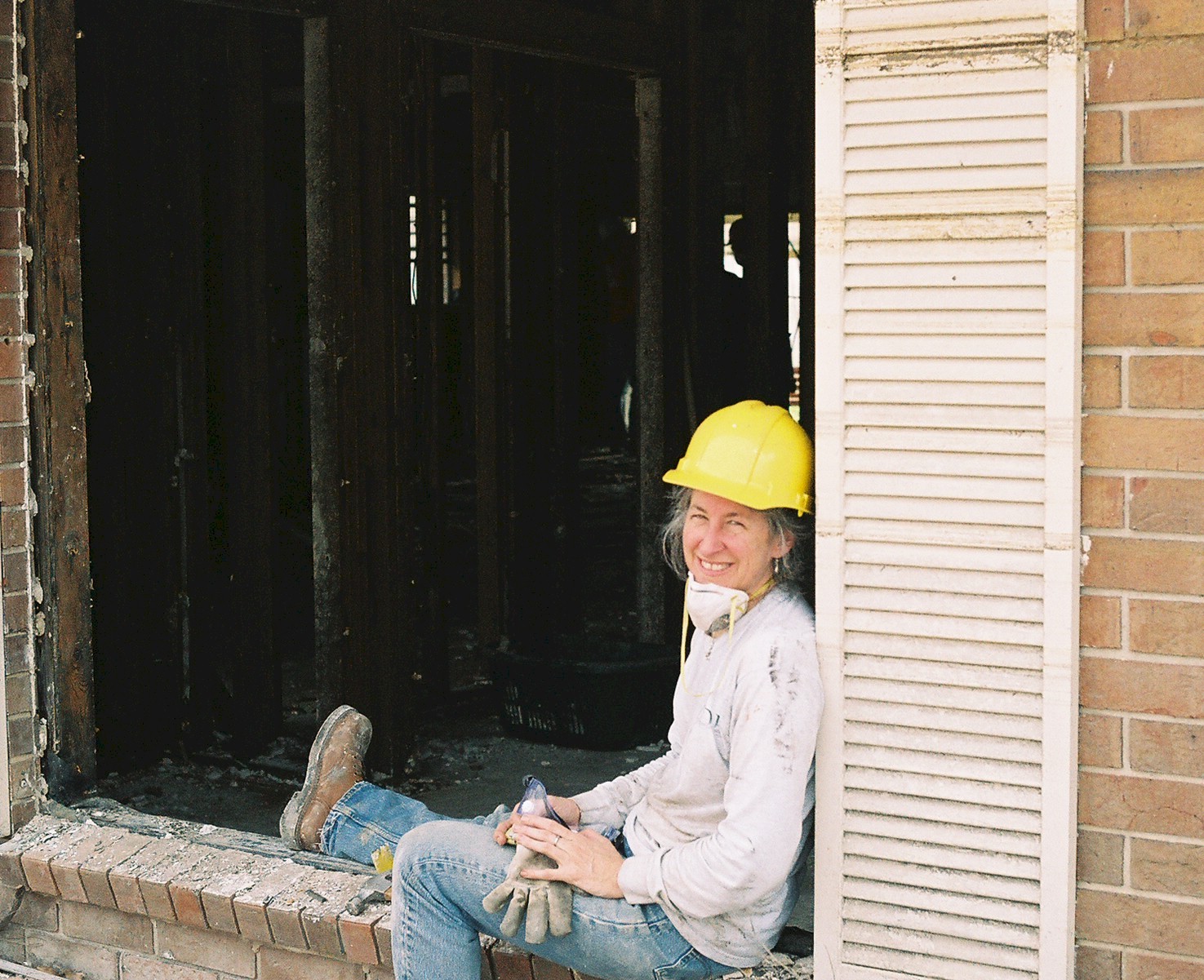

My first impression of Denise is that we could be friends. She is open, fun-loving, committed to family and community. She has lived in Chalmette her whole life, leaving her chosen field behind to join the family business as her parents aged. Her husband and children are in New York awaiting word about when they might return home and rebuild their life here. She arrived from New York a half hour after we began gutting her home; she donned a mask and gloves and joined our work team in clearing the debris that was formerly her home.

I moved away from Louisiana in 1985, the same year my parents left the last home of my childhood where they had lived for nearly fifteen years. I have returned only a handful of times; my last visit was over ten years ago. My roots have always been there, though they have slept inside me silently. Then Hurricane Katrina roared ashore and awakened them. I began reading the news from the local New Orleans paper on the web like it was again landing on my parents’ doorstep. My brother, Jim, and I began plotting together how to meet here and volunteer.

The first settlement in St. Bernard Parish dates back to around 1780. General Andrew Jackson defeated the British here in 1815 in the famous Battle of New Orleans; the memorial battlefield is a reminder of the history. Over time, much of the parish has become part of “Greater New Orleans,” though towns like Arabi and Chalmette have retained much of their individuality. Although the parish’s almost eighteen hundred square miles is seventy-four percent water, flooding here has only been truly devastating when human hands have been involved. For example, during the Mississippi River flood of 1927, dynamite was used to breach a levee to the south in order to protect the city of New Orleans, leaving most of St. Bernard flooded instead and causing widespread destruction. In 1965, the much-maligned “Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet” (“MR-GO”) waterway opened despite concerns. While it could increase shipping commerce by providing a straighter course from the Gulf of Mexico to the city, it could also very likely serve as a “hurricane highway,” funneling storm surge directly from the Gulf. Later that very year, Hurricane Betsy proved the point, bringing through the MR-GO a flood that devastated the area. Then again last fall, Hurricane Katrina swamped the area under some twenty to thirty feet of water, which remained standing for over two weeks. Many residents here now call the MR-GO, “MR-GONE,” calling for its permanent closure.

But if you ask the people of Chalmette whether they want to rebuild, for most there is no question. This is home. Many have already returned. Even though they have lost everything, their spirit is strong. Denise said that though this is the worst thing ever to happen to her family, she can’t feel singled out: it has happened to everyone here, and in this sense they are in it together. But it occurred to me as we talked that they have not just lost everything material, home and all its contents. They have lost their whole neighborhood, their community—ultimately a more intangible and profound loss and one that will take longer to rebuild. After we left her behind one afternoon to return to camp, she told us the next day how eerie it felt to be the only one present on her street. It was quiet, too quiet.

I have found the one “natural area” at camp: the bayou that divides the camp from the St. Bernard Highway; the refinery’s smokestack is to my right, as is the rising sun. The barracks-style tents are behind me. The sky is clear, and after a brief midnight rain, the temperature and humidity have dropped significantly. A Great Egret just flew by. I have met some fascinating people in this camp. I am struck by how many are here as individuals, having come on their own, using vacation time to help out. My tent alone houses a school teacher from St. Louis, an attorney from Atlanta, a physician from Wisconsin, a defense contractor from Virginia. Beyond us, the place is full of college students. Coming from all over the country to work during their spring break, they comprise probably eighty percent of the volunteer force this week. The team working across the street from us is from Missouri State, and one of them is the student who energized and mobilized a group of over one hundred students to come from her school alone.

The scope of the volunteer effort is impressive: around twelve hundred volunteers working in the neighborhoods this week—three shifts of about four hundred, twelve to fifteen people per team, five to six teams per bus, five buses. It is a logistical challenge to say the least. It is running surprisingly smoothly considering all that could go wrong. And is there ever work to do! These homes stand in ruin. We hear stories about homeowners who show up as their homes are being cleared and can only stay half an hour because of the vastness of their loss. The prospect of what lies ahead to reclaim their lives is overwhelming. They are grateful beyond words.

Yesterday was “hump day” and an emotional one for me. It started when I became absorbed in saving the Corningware out of an elderly widow’s destroyed kitchen. It was the same pattern as my mother’s. This woman was likely a child of the Depression and saved everything. The reality of her life was hard to take in: living alone and losing everything that she had so purposefully saved. Later in the day, a couple arrived at the house across the street where the Missouri State team is working. Still a distance away, they pulled over for a moment and then drove down and parked near the house. They got out of the car, took one look at the house, and the woman collapsed into the man’s arms. They composed themselves and then met the team working to clear the home. They didn’t stay long.

A team member and I walked down the street to visit with a homeowner who was working on his down-to-the-studs gutted home. He has done all the work himself: he “got tired a waitin on everybody,” so he began by himself. Meanwhile, his family is housed at Domino Sugar where he works nights. Domino Sugar has been housing their employees and families in temporary housing for nearly seven months now. This man and his family had rented their home for five years, finally purchasing it just two months before the storm. The storm surge topped the levee that is less than a block away, and it flooded up to the rafters; they lost everything. He said he took FEMA up on a trailer after the agency’s fourth offer. It occupies his front yard. He uses it for tool storage and bathroom facilities while he rebuilds. He said as we parted, “We shure do appreciated ya’ll comin down. I toll my wife, you can’t cry about it; you just got to move on. I been married twice before, lost everything before both times. I can do it again. You can’t cry about it; you just got to keep on goin.” As we walked back to work, I was the one fighting back tears.

We notice that whenever we stop where a FEMA trailer is nearby, we are more than likely invited to visit. A few trailers inhabit sections of neighborhoods together, but more often a single trailer is the sole occupant on a street. Residents in these trailers are so hungry for neighbors that we will do in a pinch. At one place, an elderly man came out to ask what we were up to. We stood next to his trailer as he eagerly shared his life story. He told us how he and his wife raised their five children here in Chalmette, in the house that stands in ruin behind him. He says it’s hard to live alone when you’re used to having people around, especially his dear wife, who died not that long ago. He is alone in his trailer and alone in his devastated neighborhood.

It is true that “it is better to give than to receive,” perhaps because much of our “receiving” is out of want and not need. And certainly it is good to give out of our abundance, if only to check our all-too-present greed and materialism. We are selfish by nature. It is important to pry our hands off of our possessions and off of our fears, our fears of going without, of not having enough.

But I am reminded of what is perhaps a corollary: “It is harder to receive than to give.” It is hard to imagine the impact of this catastrophic event on the people here. Photos and video cannot capture the scale of the devastation. Not one home was spared in a sixteen-square-mile area in St. Bernard alone. And then there is the destruction beyond us. The people of Louisiana and Mississippi have had their material goods ripped from their hands in a dramatic ordeal of pain and loss.

Denise and her family have relocated for now to a foreign country called upstate New York. She considers herself lucky: her husband has a contract job and therefore a place for them to go. This cannot be said of most of her neighbors. But she wants to come home. She wants to rebuild the house where they have been raising their three children for eight years. Through tears, she shared how incredibly humbling it is to receive our help. Her vulnerability and need are exposed to such a great extent that all she can do is gratefully receive. In spite of this, she provided gift bags of specialty New Orleans treats to all thirteen members of our team before we left. And she gave to us more than she knew—by welcoming us into her home and into her heart.

The truth is that we all need. We need each other to help in times of severe difficulty, and we also need each other when things are going well. But even in our need, we each have a great deal to give and to share with one another. Our needs are deep, and so is our capacity to give. In the process of compassionately giving and humbly receiving, we are given perspective on our vulnerability and on the reality of our position as creatures. The challenge lies in accepting our place from God as we both give and receive. And in this way, we live in humble dependence on God and each other.