One of my favorite quotes about literature comes from British author C.S. Lewis, who once wrote that “What we want is not more little books about Christianity, but more little books by Christians on other subjects—with their Christianity latent.”

The word latent comes from latēre, which in Latin means “to lie hidden,” as when something is “present but not visible, apparent, or actualized.” The word reminds me of Søren Kierkegaard’s philosophical concept of indirect communication, which “was designed to sever the reliance of the reader on the authority of the author,” according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. “The point of indirect communication is to position the reader to relate to the truth with appropriate passion, rather than to communicate the truth as such.”

As both an author and Gutenberg graduate, I couldn’t agree more with that concept in today’s media-saturated, results-driven, unreflective world. Just look at the explosion of “Christian” literature both online and in traditional bookstores that touts everything from Adulting 101: #Wisdom4Life (Josh Burnette) to Next Level Thinking: 10 Powerful Thoughts for a Successful and Abundant Life (Joel Osteen).

While these types of self-help books can have their place, as direct forms of communication they often lack the depth and reflection that C.S. Lewis was calling Christians to when they set pen to paper. Too many Christian authors today focus so much on surface-level facets of the Christian life that they fail to address those deeper and more pressing subjects facing the world today.

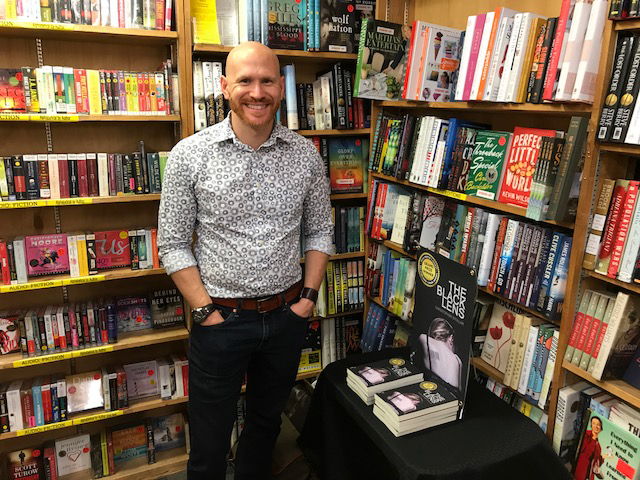

That’s why I decided to research, write, and publish a novel about one of those subjects: human trafficking. The Black Lens is a dark literary thriller that exposes the underbelly of sex trafficking in rural America. While my book is fiction, I strove to write deeply about the real world in an indirect, latent, and authentic way that wasn’t explicitly “Christian.” In fact, one of the most common questions I get from readers is why I as a believer decided to write about such a dark topic in the first place. It’s a great question and one I’ve reflected on ever since I started researching the subject more than five years ago. So, below are my three main reasons for writing The Black Lens.

To raise trafficking awareness

I have always wanted to use my story to raise awareness about sex trafficking. While this topic has received more press in the last few years, some people still don’t think trafficking happens often in the United States. But nothing could be farther from the truth.

The National Human Trafficking Hot-line has documented at least 45,308 trafficking cases since 2007. It’s a harsh fact, but that’s why raising awareness is so key. And it’s why I decided to conduct more than three years of research on this subject. As a former reporter with a master’s degree in journalism, I personally interviewed more than a dozen survivors, social workers, and police officers.

That research paid off. During the past few years, several readers have told me they wanted to become more involved in fighting trafficking as a result of reading my debut novel. But the best feedback came from one recent Amazon reviewer—who is also a Gutenberg graduate. She said reading The Black Lens opened her eyes to this underground world and actually helped her prevent a potential trafficking situation:

Since reading this, I have become more aware of the issues and the prevalence of human sex trafficking and have recently witnessed an (incident) at Disneyland Shopping District of someone preying on a young teen sitting alone waiting for her parents to finish shopping. I stepped in and made sure she was not alone and not targeted by the man asking her inappropriate questions and inviting her to help him with his bags to his car.

The reviewer continues:

I enjoyed the story line and the characters, but what I appreciated the most was the movement to bring the sinister world of sex trafficking into our awareness so that more can be done to protect our youth and change our own story line as a culture (that) does not allow the opportunity for these crimes to become a reality for future at-risk youth.

As an author, I couldn’t ask for anything more.

To take sin seriously

When you consider recent Christian literature—whether fiction or nonfiction—much of it doesn’t take sin seriously. These books focus so much on the truth of grace that they hide from the truth of evil. And yet if you spend any time reading the Old Testament, you discover that it’s filled with descriptions of evil. There is rape, incest, even torture. None of the authors glorified those crimes or described them in graphic detail, but they also didn’t shy away from them either. Why? Because they were trying to contrast the depth of man’s evil with the depth of God’s grace.

One of my favorite Christian authors from Gutenberg’s curriculum is Flannery O’Connor, who became famous for her dark, brutal, and violent short stories. She once wrote, “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.” That’s great advice for every Christian writer. We need to contrast good and evil if we want to have any chance at engaging the world with our words—especially with such dark topics like sex trafficking.

To engage the arts

As created beings, Christians have so much to contribute to the arts—especially in the area of writing. For centuries, believers were at the forefront of art and culture. The Catholic Church sponsored some of the most famous artists of all times, such as Michelangelo. But for decades, Christians have retreated from the arts. I don’t know all the reasons, but author Francis Schaeffer (another one of my favorites from Gutenberg) once wrote, “I am afraid that as evangelicals, we think that a work of art only has value if we reduce it to a tract.”

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis compares friendship with art, philosophy, and the universe, all of which are “unnecessary” and have “no survival value,” but each of which “is one of those things which give value to survival.” Literature is a form of art, so it too has no inherent survival value. But literature can give value to survival in unique and powerful ways. Think of the impact behind literature like Uncle Tom’s Cabin or To Kill a Mockingbird. Those latent novels affected so many people’s views of race and slavery in ways that direct communication never could.

One of my favorite books in the Bible is Esther because it reads like a work of modern fiction. It features a strong female heroine, romantic suspense, and even a murder plot. But most interestingly, the book doesn’t mention God once. Yet for those who have eyes to see, every sentence in the story points to God and gives value to the idea of surviving suffering.

My goal for The Black Lens was the same. I wrote it in an indirect and latent way for those who have eyes to see.

This article first appeared in the Winter 2019 issue of Colloquy, Gutenberg College’s free quarterly newsletter. Subscribe here.